Standardising health and climate metrics to drive urgent action

Wellcome is funding the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) to develop metrics to measure, monitor and track the impact the climate crisis is having on our health.

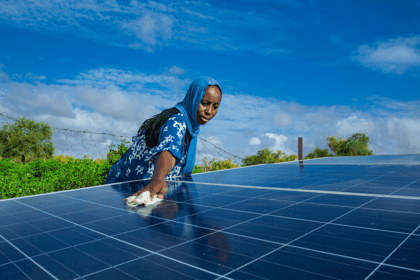

Lys Arango

Mario’s family leave their community in San Miguel Acatán in search of work. Drought and shifting weather have made farming unworkable locally, so they need to look elsewhere to feed their children.

About this series

Increasingly erratic climate patterns have produced year after year of failed harvests in Guatemala, forcing thousands of people to migrate, trying to escape poverty and malnutrition.

Lys Arango / Wellcome Photography Prize 2021

Health metrics are essential. Just look at the last two years.

When used properly, official statistics based on reliable metrics can lead to clearer communication, directed policy, and ultimately, progress. But we think one area is largely neglected – measuring how climate change is affecting our health.

With support from Wellcome, the ONS will change this by defining interpretable and meaningful statistics.

“We are delighted to be working with Wellcome on a new four-year project aimed at moving the global knowledge base on climate change and health forwards from exploratory academic research towards robust and transparent official statistics that will inform national and local decisions in a number of countries.”

Why we need better metrics and statistics

Research is stimulated by important questions and challenges, which are often underpinned by metrics and statistics.

But what happens when those metrics don’t provide a clear view of what's happening?

During the UN’s 26th annual climate change conference (COP26), climate-related statistics were widely discussed – from ‘global surface temperature’ to ‘carbon emissions’ – and used to set goals for achieving ‘net zero’ carbon emissions by 2050.

Such targets might appear abstract, but they are crucial for governments, policymakers and researchers to investigate methods for reducing emissions and quantifying successes easily.

But if we focus solely on forecasting and the distant future, it becomes clear that our current measures and targets aren’t sufficient.

For example, setting a target for carbon reductions is an important goal for high-income countries.

But it misses the millions of people, mainly in low- and middle-income countries, who are already experiencing the health impacts of climate change.

So, we need data to show what’s happening right now.

Without it we can’t compare how the climate crisis is impacting health at a global level, which leads to disjointed research, communication challenges and makes agenda-setting impossible.

The data just isn’t being collected

Right now, there isn’t a universally recognised set of standards for reporting the impacts of climate change on health, which affects international monitoring and collaboration.

Take deaths for example.

Climate and weather are never referenced on death certificates. In fact, the first reference to air pollution on a UK death certificate was recorded in 2020.

Official data collection channels do not capture what is required to report these types of statistics.

This issue is worse in many low- and middle-income countries where fewer than one in ten deaths are even recorded by national statistics agencies.

Better statistics can lead to better health policies

With £5 million in funding from Wellcome, over the next four years, the ONS will generate tools to measure and define methods to report the impacts of climate change on health.

This will be done in partnership with two low- and middle-income-based national statistics agencies to co-develop a partnership where impacts of climate change are most likely to be experienced.

The ONS will:

- Examine the role of real-world data sources – for example, census data to understand exposure patterns at a population level and determine how to record deaths that are caused by climate change.

- Develop and convene national statistics agencies around a framework for official statistics on climate change, the environment and health.

- Create a set of statistical methods that better estimate climate-related health risks using real-world data sources.

Instead of goals to prevent temperatures from rising by 1°C in certain countries, policymakers could consider more actionable and immediate targets. This could be ensuring adequate hydration and access to clean water in low- and middle-income countries that have rising temperatures.

But without good data to inform this, it’s easier said than done.

Research shows that hot nights lead to higher rates of heat-related deaths in older people, whereas hot days are more likely to cause death in younger people, who may be working outside in extreme conditions.

So instead of only reporting ‘average daytime temperature’, researchers and scientists need more detailed measures – such as average daytime and night-time temperatures. On top of this, records need to show the number of day- and night-time deaths across different ages.

With better measures we can illustrate the true health impacts of climate change.

And policymakers can then focus their efforts on solving them.